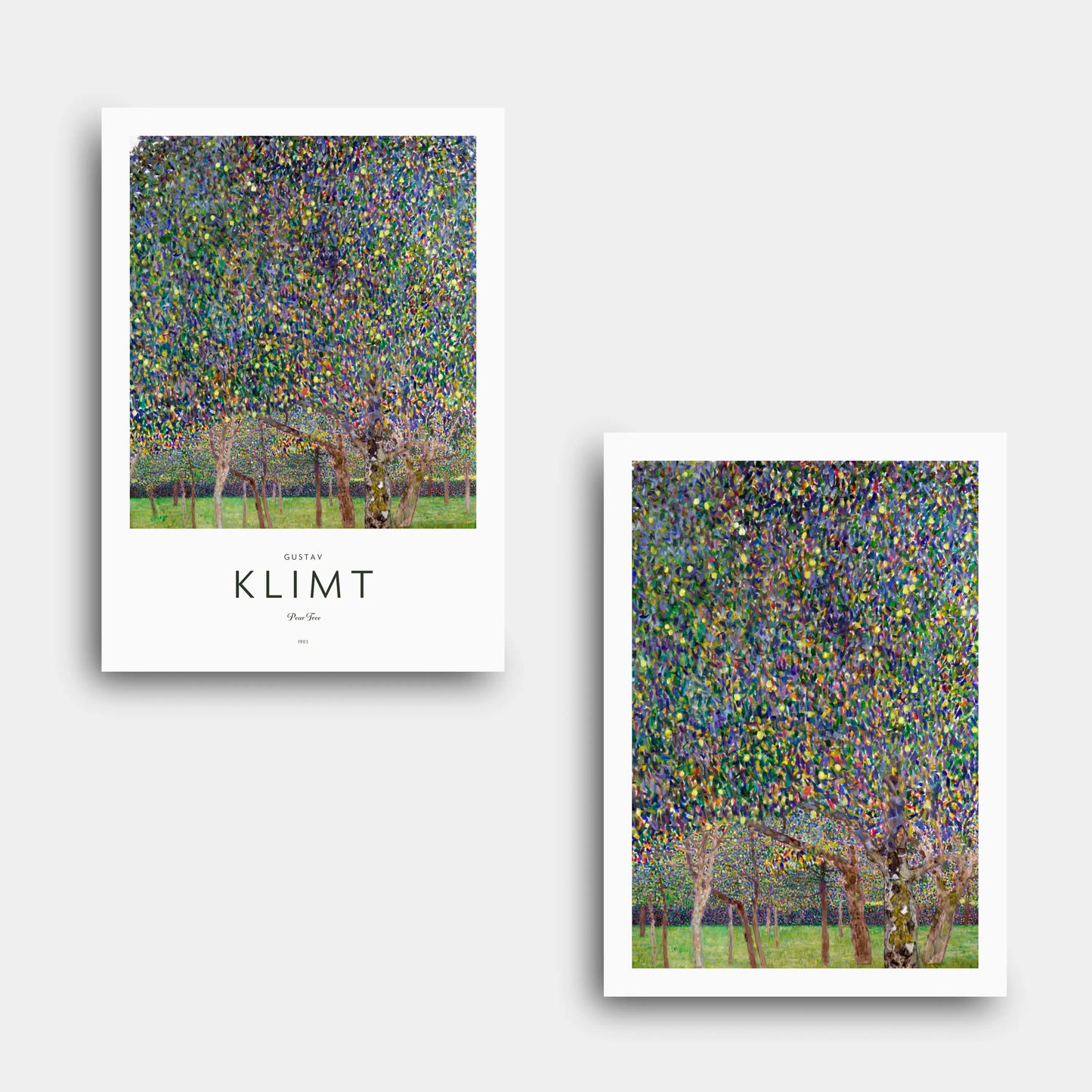

Gustav Klimt - Pear Tree (1903) - Digital File N185

Gustav Klimt - Pear Tree (1903) - Digital File N185

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Paper Poster | Canvas Print | Digital File

1. Historical and Artistic Context

Gustav Klimt painted “Pear Tree” in 1903, during his summer retreats at Lake Attersee in Austria. These annual journeys provided him with the tranquility and inspiration to focus on landscapes, which became an essential part of his oeuvre. The early 1900s marked a period of transition in Klimt’s career, as he was moving from the ornamental qualities of his Golden Phase into a more painterly exploration of nature. The “Pear Tree” reflects this moment, combining decorative symbolism with fresh observation of the natural world. It also illustrates the influence of the Vienna Secession movement, which sought to liberate art from academic traditions and merge fine and applied arts into a unified aesthetic vision.

2. Technical and Stylistic Analysis

The painting is notable for its dense and mosaic-like composition. Klimt used countless dabs and strokes of paint, creating a surface that almost dissolves into abstraction. The tree’s canopy fills the canvas from edge to edge, with only small patches of sky and ground visible, emphasizing the ornamental quality. This flattening of space recalls Byzantine mosaics, a major source of inspiration for Klimt. At the same time, the application of vibrant, contrasting colors in small strokes demonstrates his engagement with pointillism and post-impressionist techniques. The square format of the canvas further enhances its decorative symmetry and reinforces its connection to modern design principles.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

“Pear Tree” symbolizes abundance, fertility, and the cycles of nature. The full canopy, alive with green, yellow, red, and purple tones, can be read as a celebration of life and renewal. Klimt’s decision to eliminate most of the sky and horizon suggests that the tree itself is a universe of vitality, enclosing the viewer in a self-contained world of color and growth. The orchard setting also conveys a sense of harmony and timelessness, linking human cultivation of nature with spiritual reflection. The pear tree, specifically, is often associated with prosperity and nourishment, adding another layer of meaning to Klimt’s symbolic vision.

4. Technique and Materials

Klimt painted this work in oil on canvas, applying paint in small, deliberate strokes that build up into dense clusters of color. The technique reflects his interest in the optical effects of juxtaposed hues rather than smooth blending. The pointillist influence is evident, but Klimt used it in a decorative rather than scientific manner, prioritizing the ornamental shimmer of the surface over color theory. The square canvas, measuring approximately one meter on each side, emphasizes balance and harmony. Klimt often preferred square formats for his landscapes, as they eliminated traditional perspective and gave equal importance to all areas of the composition.

5. Cultural Impact

The painting stands as a key example of Klimt’s contribution to modern landscape art. By treating the tree as both a natural subject and an ornamental surface, he bridged the gap between fine art and decorative art, a central ambition of the Vienna Secession. “Pear Tree” influenced how later generations approached landscape painting, particularly in the way it combined symbolism with abstraction. It has been referenced in discussions of early modernism as an artwork that challenges the boundary between figuration and pattern, helping redefine what a landscape could represent in the 20th century.

6. Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Although Klimt was primarily known for his portraits, critics and scholars later recognized the originality of his landscapes. “Pear Tree” has been described as a tapestry of color, a “wall of nature” that transforms a simple orchard into a decorative icon. Scholars highlight how the painting embodies both Symbolist and modernist tendencies: symbolic in its focus on abundance and fertility, modernist in its use of flatness and vibrant color. Art historians also interpret it as part of Klimt’s personal world, reflecting the serenity he sought during his summers away from Vienna’s cultural turbulence.

7. Museum, Provenance and Exhibition History

Klimt gifted “Pear Tree” to Emilie Flöge, his lifelong companion, shortly after completing it in 1903. Later it entered the collection of the art dealer Otto Kallir, who played a crucial role in promoting Klimt’s work internationally. Today the painting belongs to the Harvard Art Museums, where it forms part of the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s distinguished holdings of Austrian modernism. It has been exhibited widely, including at the Venice Biennale in 1910 and in later retrospectives devoted to Klimt’s landscapes, reaffirming its importance as a masterpiece of his landscape production.

8. Interesting Facts

1. Klimt painted most of his landscapes at Lake Attersee during summer holidays.

2. The square format of “Pear Tree” was unusual at the time and linked to Japanese print aesthetics.

3. The painting was originally gifted to Emilie Flöge, Klimt’s partner.

4. Klimt did not use gold leaf in this landscape, unlike his portraits.

5. The composition eliminates traditional perspective, emphasizing flatness.

6. Klimt was influenced by pointillism but used it decoratively, not scientifically.

7. The tree dominates the canvas, with almost no sky visible.

8. It was shown at the 1910 Venice Biennale, marking its early international exposure.

9. The work is now housed at Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum.

10. Klimt’s landscapes were created for his own pleasure, unlike his commissioned portraits.

9. Conclusion

“Pear Tree” represents a perfect synthesis of Klimt’s ornamental tendencies and his fascination with nature. By transforming a simple tree into a vibrant, abstract tapestry, Klimt demonstrated how modern art could reimagine traditional subjects through color, pattern, and symbolism. The work stands as a testament to his unique vision, bridging the decorative language of the Vienna Secession with the experimental approaches of post-impressionism. Today, it remains one of his most celebrated landscapes, admired for both its visual richness and its deeper symbolic resonance.