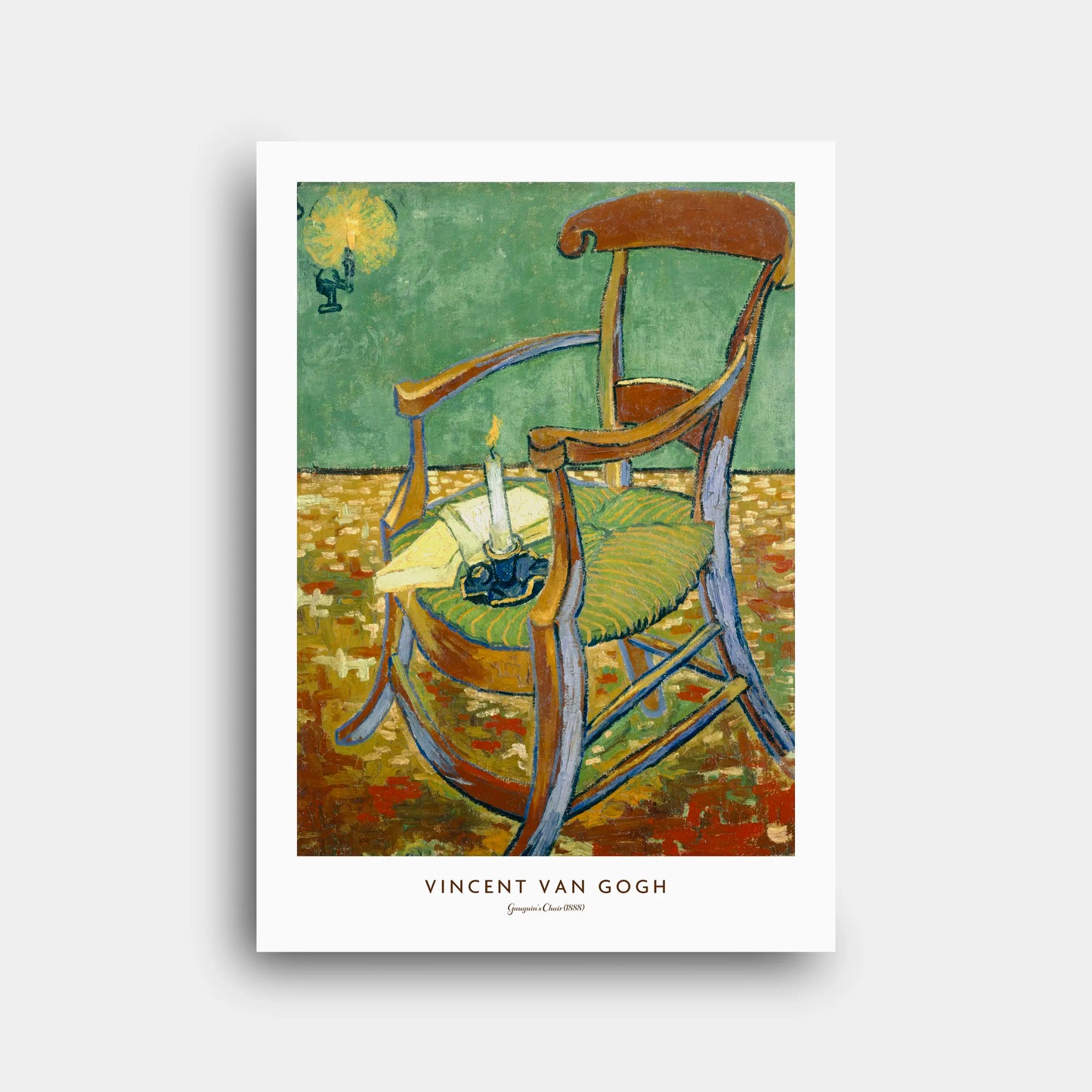

Vincent van Gogh - Gauguin’s Chair (1888) - Paper Poster N206

Vincent van Gogh - Gauguin’s Chair (1888) - Paper Poster N206

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Paper Poster | Canvas Print | Digital File

1. Historical and Artistic Context

Vincent van Gogh painted Gauguin’s Chair in November 1888 in Arles, during the brief but intense period when he lived and worked with Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh envisioned the “Studio of the South” as a collective workshop, and Gauguin’s arrival in the Yellow House marked the peak of that dream. Instead of conventional portraits, Van Gogh symbolized himself and Gauguin through chairs: his own simple straw chair bathed in daylight and Gauguin’s more ornate armchair illuminated by candlelight at night. These pendant works expressed their contrasting temperaments and artistic identities. The paintings were created before their quarrels escalated, yet in hindsight, they came to represent the tensions and eventual rupture of their collaboration.

2. Technical and Stylistic Analysis

The painting depicts a carved wooden armchair with curved arms, a green cushion, two novels, and a lit candle. The composition tilts slightly forward, pulling the viewer into the space. The palette is dominated by complementary contrasts—reds and greens, yellows and blues—producing a vivid and tense atmosphere. The floor is built from dabs of ochre, brown, and green, while the wall is cool green with a mounted gas lamp. Van Gogh’s brushwork is vigorous: the cushion is formed by curved strokes, the floor by short blocks of color, and the contours of the chair are outlined with blue against red-brown. The impasto is heavy, creating texture and vitality.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

The ornate armchair symbolizes Gauguin’s sophistication and cultivated persona, contrasting Van Gogh’s humble straw seat. The novels represent Gauguin’s intellect and connection to modern ideas, while the candle embodies his creative flame and affinity for night. The whole scene functions as a symbolic portrait, suggesting presence through absence. Together with Van Gogh’s Chair, the work dramatizes differences: Gauguin as mysterious, intellectual, nocturnal; Van Gogh as grounded, plain, and linked to daylight. Later interpretations layered new meanings, with some critics reading the empty chair as foreshadowing absence, though recent scholarship emphasizes its original playful and optimistic intent.

4. Technique and Materials

The painting is oil on canvas, approximately 90 × 70 cm. Van Gogh used a standard French “size 30” canvas. The paint was applied thickly, with rich impasto enhancing the tactile qualities of wood, cushion, and flame. Outlines in contrasting hues sharpen forms and intensify color vibration. Van Gogh exploited complementary contrasts: red-green for tension and yellow-blue for luminosity. Brushstrokes remain visible, embodying the artist’s urgency and expressiveness. The candle’s small flame is a thick dash of bright pigment, glowing against the darker interior, exemplifying Van Gogh’s ability to render light with paint alone.

5. Cultural Impact

Gauguin’s Chair has become emblematic of Van Gogh’s symbolic approach to portraiture. The motif of the empty chair resonates widely as a metaphor for presence-in-absence, memory, and identity. Lucian Freud later remarked, “Everything is autobiographical and everything is a portrait, even if it’s a chair,” highlighting its influence. The work contributes to the dramatic narrative of Van Gogh and Gauguin’s collaboration, quarrel, and separation. Beyond its biographical context, it stands as a landmark in modern art’s exploration of everyday objects as vessels of psychological and symbolic meaning.

6. Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Initially overshadowed by Van Gogh’s Chair, this painting was not exhibited until 1928 due to Johanna van Gogh-Bonger’s dislike of Gauguin. Once revealed, scholars debated its meaning. Some saw it as a mournful symbol of absence; others emphasized the contrast of personalities. Psychoanalytic readings even suggested sexual connotations in the candle imagery. Recent research by Louis van Tilborgh corrected earlier misdatings and argued the chairs were painted in a spirit of optimism rather than despair. This shift highlights Van Gogh’s playful, experimental intent, while acknowledging the tragic connotations later attached to the work.

7. Museum, Provenance and Exhibition History

After completion, the painting went to Theo van Gogh in Paris, then to Johanna. She withheld it from exhibitions for decades, and it only debuted publicly in 1928. It was later lent to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and in 1962 entered the Van Gogh Foundation. Since 1973, it has been on permanent loan to the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, where it remains today. Its pendant, Van Gogh’s Chair, resides in the National Gallery, London. Rare exhibitions have reunited them, but most often they are displayed separately, emphasizing their divergent meanings.

8. Interesting Facts

1. Painted in November 1888 during Gauguin’s stay in Arles.

2. Considered a symbolic portrait rather than a literal one.

3. The ornate armchair was the only such chair Van Gogh bought for the Yellow House.

4. The novels’ exact titles remain unidentified.

5. Johanna van Gogh-Bonger disliked Gauguin and kept the work hidden for decades.

6. Public exhibition began only in 1928.

7. It measures about 90 × 70 cm, a “size 30” canvas.

8. The companion painting is in London’s National Gallery.

9. Van Gogh described the paintings as “funny” or “curious.”

10. Lucian Freud admired them as autobiographical portraits.

9. Conclusion

Gauguin’s Chair distills Van Gogh’s genius for transforming the ordinary into the symbolic. Through a chair, books, and a candle, he evoked Gauguin’s intellect, sophistication, and creative flame. In contrast with his own chair painting, it dramatized differences in character and vision. Though later interpreted as a symbol of absence, its original intent was playful and hopeful. Today, it stands as a key work in Van Gogh’s Arles period, a testament to friendship, conflict, and the expressive power of everyday objects to embody human presence and identity.