Vincent van Gogh - Oleanders (1888) - Paper Poster N200

Vincent van Gogh - Oleanders (1888) - Paper Poster N200

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Paper Poster | Canvas Print | Digital File

1. Historical and Artistic Context

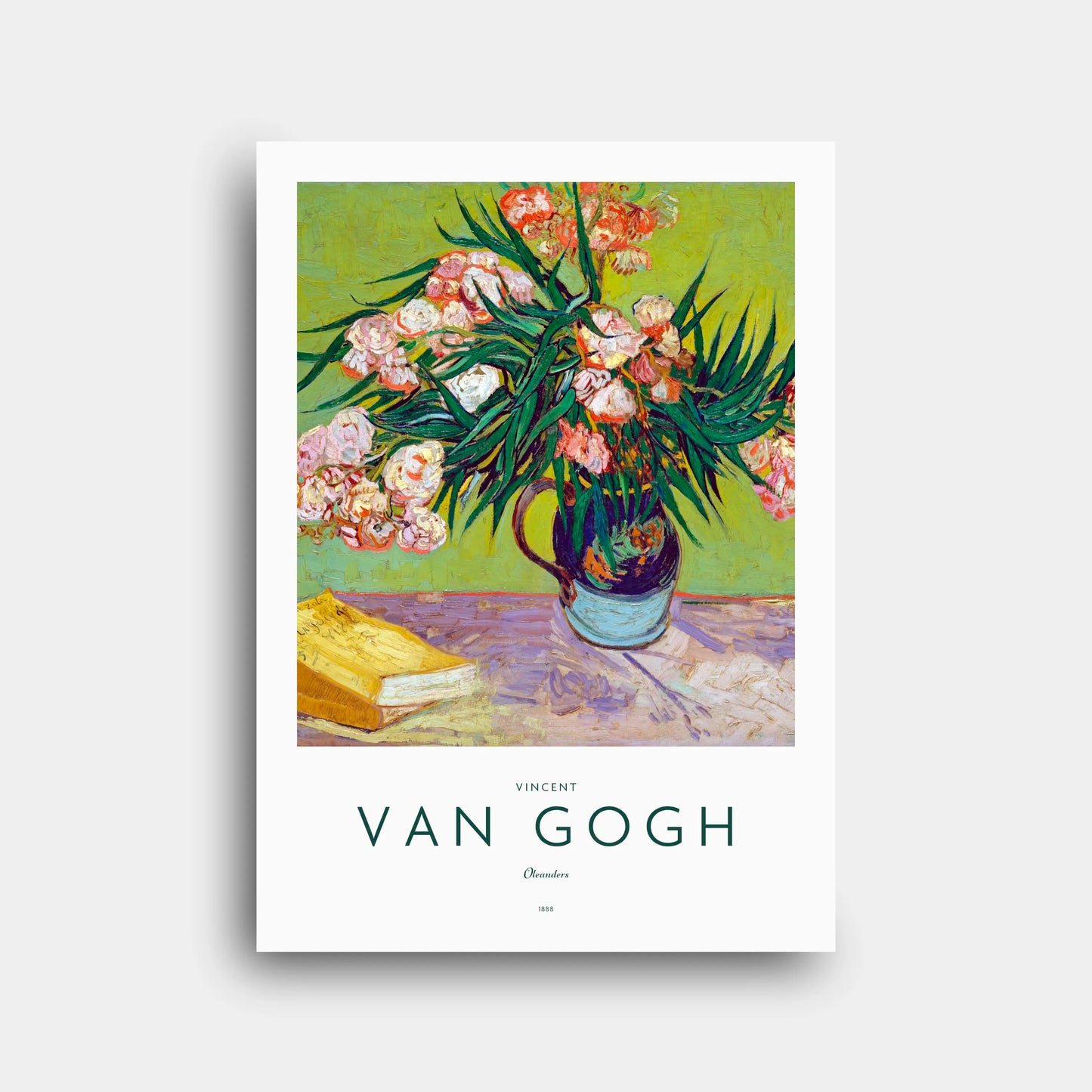

Vincent van Gogh painted Oleanders in August 1888 while living in Arles, in the south of France. This was one of the most productive phases of his career, marked by luminous colors and bold experimentation. Arles offered him the light and intensity he sought after leaving Paris, and he immersed himself in still lifes, portraits, and landscapes. Oleanders emerged as part of his exploration of floral motifs, alongside the famous Sunflowers. At this moment, Van Gogh was inspired by the idea of building an artistic community in the Yellow House, anticipating Gauguin’s arrival and dreaming of collective creativity.

2. Technical and Stylistic Analysis

The painting demonstrates Van Gogh’s vigorous brushwork and thick application of paint, or impasto. The oleander blossoms are rendered with swirling strokes, while the elongated green leaves are defined with sharp lines. Against a glowing green background, the blossoms radiate energy and vibrancy. The yellow book anchors the lower half of the composition, balancing the exuberant flowers with geometric stability. Van Gogh’s palette features complementary contrasts: pink and green, yellow and violet. These bold chromatic choices heighten the expressive force of the work, making the flowers appear alive and pulsating with vitality, while the book introduces intellectual resonance.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

Oleanders are resilient plants, thriving in difficult conditions, and Van Gogh used them to symbolize endurance and joy. Unlike the wilting Sunflowers that suggest mortality, these blossoms affirm the continuity of life. The book beside the vase, identified as Émile Zola’s La Joie de vivre, underscores this theme by representing the resilience of the human spirit. Together, flowers and book merge natural vitality with cultural depth. At the same time, oleanders are poisonous, reminding the viewer that beauty often coexists with danger. This duality mirrors Van Gogh’s own life, torn between radiant artistic creation and inner suffering.

4. Technique and Materials

The artwork was executed in oil on canvas, measuring about 60 by 73 centimeters. Van Gogh used modern pigments in tubes, which allowed him to create vibrant greens, yellows, and pinks. He applied paint thickly, layering colors to produce luminosity and texture. The petals were formed with curved strokes, the leaves with angular ones, and the background with broader, flatter applications of paint. The vase, a piece of majolica pottery, grounds the composition in darker tones. Careful detail is given to the yellow book, where Van Gogh inscribed Zola’s name and title, highlighting its symbolic importance within the composition.

5. Cultural Impact

Although less famous than Sunflowers or The Starry Night, Oleanders has an essential role in Van Gogh’s oeuvre. It is often cited as a counterpart to Sunflowers, embodying vitality rather than mortality. The work reinforces Van Gogh’s reputation as an artist who could transform everyday still life into a profound meditation on existence. Over the years, it has been reproduced in countless forms and continues to inspire audiences with its affirming message. Its presence in exhibitions highlights Van Gogh’s ability to fuse color, symbolism, and emotional intensity into works that transcend their modest subject matter.

6. Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Scholars interpret Oleanders as one of Van Gogh’s most optimistic still lifes. The book’s inclusion has been seen as a declaration of philosophical alignment with Zola’s naturalist vision, affirming life despite hardship. Critics point out the balance between exuberant organic forms and structured geometry, which anticipates aspects of modernism and even cubism. While not as universally recognized as other Van Gogh masterpieces, Oleanders has received attention for its symbolic contrasts: joy and danger, vitality and fragility. It is now understood as a pivotal work that reflects Van Gogh’s capacity to infuse still life with profound emotional resonance.

7. Museum, Provenance and Exhibition History

The painting entered The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1962, donated by John and Marjorie Loeb. Before this, it passed through private collections. Today, it hangs in Gallery 825, where it continues to attract visitors as one of the highlights of the museum’s Van Gogh holdings. Oleanders has been featured in numerous exhibitions on post-impressionism and Van Gogh retrospectives, often displayed alongside Sunflowers to illustrate thematic contrasts. The Met has also studied the painting’s materials and conservation, confirming the remarkable vibrancy of its pigments more than a century after its creation.

8. Interesting Facts

1. Van Gogh mentioned his plan to paint oleanders in a July 1888 letter to Theo.

2. The yellow book is Émile Zola’s La Joie de vivre, painted with visible lettering.

3. Oleanders are poisonous, adding symbolic tension to their beauty.

4. The painting contrasts with Sunflowers, representing vitality instead of mortality.

5. The composition juxtaposes organic forms with geometric order.

6. The vase is majolica pottery, similar to others used in Arles still lifes.

7. A second version of Oleanders existed but was lost during World War II.

8. Van Gogh called oleanders “life-affirming flowers” in his correspondence.

9. The work has been in the Met since 1962 as a donation.

10. Conservation shows the pigments remain exceptionally bright today.

9. Conclusion

Oleanders is a vibrant statement of resilience and joy, painted at a moment of great hope in Van Gogh’s life. The exuberant blossoms, paired with Zola’s novel, convey affirmation of life despite adversity. The vigorous brushwork, luminous palette, and symbolic depth make it a quintessential Van Gogh work, embodying his ability to transform still life into philosophical meditation. Today, as part of the Met’s collection, it continues to captivate audiences with its radiant beauty and timeless message. It stands as proof that Van Gogh could find joy and strength even in the most ordinary of subjects.