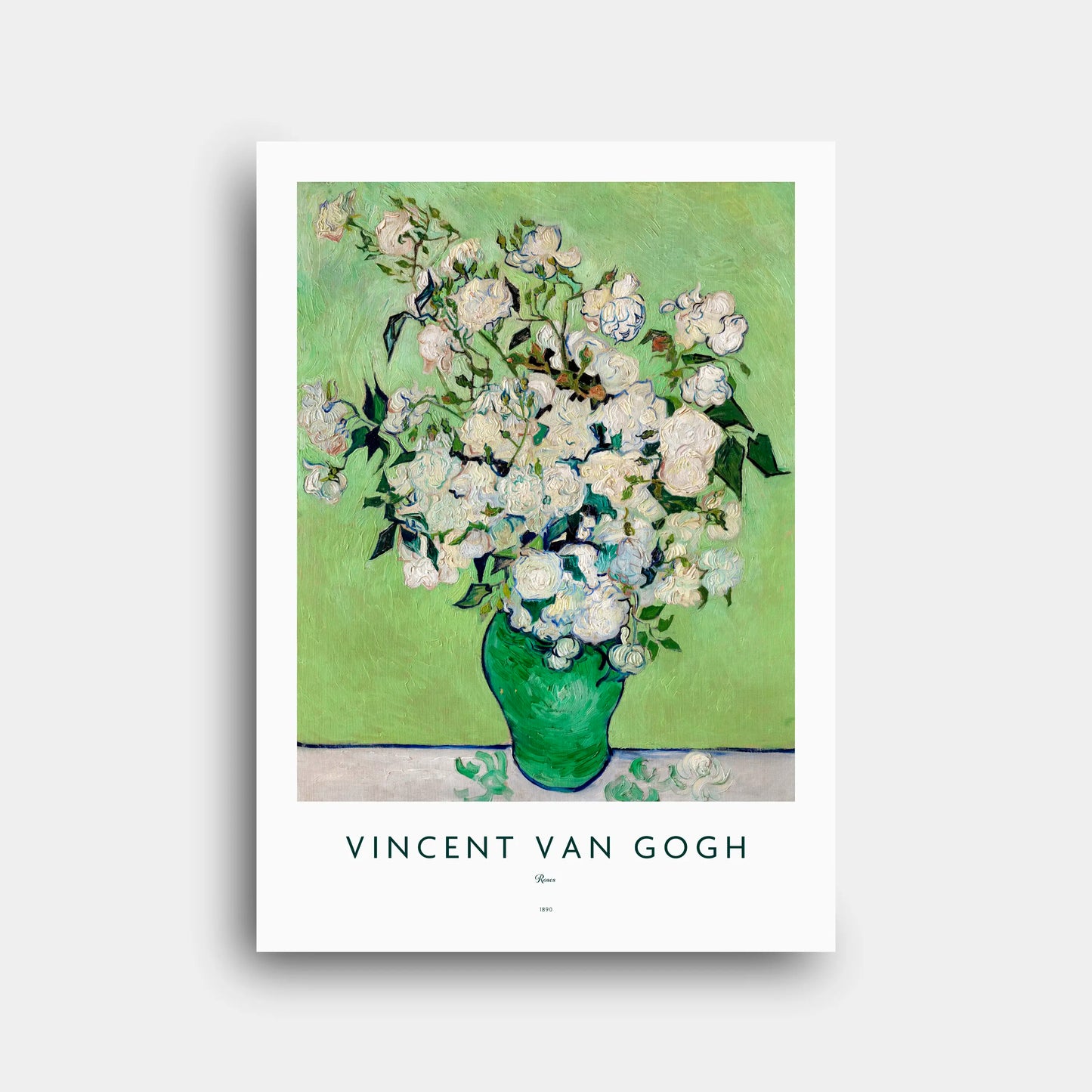

Vincent van Gogh - Roses (1890) - Paper Poster N197

Vincent van Gogh - Roses (1890) - Paper Poster N197

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Paper Poster | Canvas Print | Digital File

1. Historical and Artistic Context

Vincent van Gogh painted "Roses" in May 1890, during his final weeks at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. It was part of a quartet of large floral still lifes, including two paintings of irises and two of roses, conceived as a farewell to his Provençal period. At that time, Van Gogh was recovering from a severe mental health crisis and preparing to move to Auvers-sur-Oise. This period marked a brief but powerful return of creative clarity. He described feeling calm and serene while painting, and the "Roses" series emerged from this fleeting sense of peace and renewal.

2. Technical and Stylistic Analysis

"Roses" exemplifies Van Gogh’s mature Post-Impressionist style. The painting presents a lush bouquet spilling from a green vase on a table, with petals falling naturally onto the surface. The brushwork is energetic and textural, characterized by swirling strokes and bold outlines. The composition is lively yet harmonious, with a soft green background that complements the original pink hue of the roses—now faded to white. Van Gogh’s signature impasto technique gives the flowers a three-dimensional feel. The arrangement appears spontaneous, but it is carefully balanced and rhythmically organized.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

Though Van Gogh didn’t assign explicit symbolism to "Roses," the painting radiates themes of hope, renewal, and the fragility of life. The fresh blooms suggest a new beginning, possibly reflecting the artist’s emotional uplift as he prepared to leave the asylum. At the same time, the fallen petals hint at the impermanence of beauty and the passage of time. The original color harmony—pink against green—enhanced the feeling of spring’s vibrancy. Viewers often interpret the piece as an emotional self-portrait, capturing a moment of clarity before Van Gogh’s final months.

4. Technique and Materials

Van Gogh used oil on canvas with a high degree of impasto, applying thick layers of paint with swift, directional strokes. He chose delicate red lake pigments for the roses, which have since faded to white due to their instability. The background features soft diagonal strokes in shades of green, adding depth and movement. Van Gogh ordered specific fine brushes to capture the layered texture of the petals. The painting’s composition also shows his mastery of color theory, as he deliberately paired complementary tones to enhance visual impact and emotional resonance.

5. Cultural Impact

"Roses" has become one of Van Gogh’s most admired still lifes, widely reproduced and referenced in both academic and popular contexts. It offers a quieter, more meditative image of the artist, contrasting the myth of Van Gogh as solely tortured and chaotic. The painting has influenced countless floral artworks and continues to captivate audiences through exhibitions and scholarly publications. Its emotional subtlety and visual serenity contribute to a broader appreciation of Van Gogh’s range, presenting him as not only expressive and intense but also capable of delicate, controlled beauty.

6. Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Critics and art historians view "Roses" as a significant late work that highlights Van Gogh’s command of color, form, and emotion. It has been praised for its serene mood and technical excellence. Scholars note how it marks a transition from Van Gogh’s high-contrast Arles period to a softer, more harmonious palette. Recent pigment studies and digital reconstructions have helped restore our understanding of the painting’s original vibrancy. The work is now interpreted not just as a still life, but as a reflection of Van Gogh’s internal state—a moment of peace before his tragic end.

7. Museum, Provenance and Exhibition History

There are two main versions of "Roses" painted in May 1890. The horizontal version is held by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the vertical version is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Both passed through significant collections and were recognized for their importance early in the 20th century. One version was even seized by the Nazis during World War II and later restituted. In 2015, both versions were reunited in a landmark exhibition at The Met, along with Van Gogh’s companion irises, allowing viewers to experience the entire floral series together.

8. Interesting Facts

1. The roses were originally pink but have faded to white due to pigment instability.

2. Van Gogh painted them just days before leaving the asylum.

3. He considered this series a continuation of his earlier sunflower paintings.

4. The paint was so thick it took over a month to dry.

5. The green vase was likely borrowed from the asylum’s garden.

6. Van Gogh used fine fitch brushes for delicate petal work.

7. The composition mirrors Japanese woodblock aesthetics.

8. One version was looted by the Nazis during WWII.

9. The paintings were reunited in a major 2015 exhibition.

10. Van Gogh described feeling “absolutely serene” while painting them.

9. Conclusion

"Roses" (1890) is a masterpiece of calm, grace, and painterly expression. Painted during a rare moment of serenity in Van Gogh’s life, it captures the spirit of renewal and fragility in a way that still resonates deeply. The technical brilliance, thoughtful composition, and symbolic richness of the work reveal an artist in full command of his vision. Today, "Roses" stands not only as a floral still life, but as a personal and poetic farewell to a chapter of Van Gogh’s life, and ultimately, to life itself.