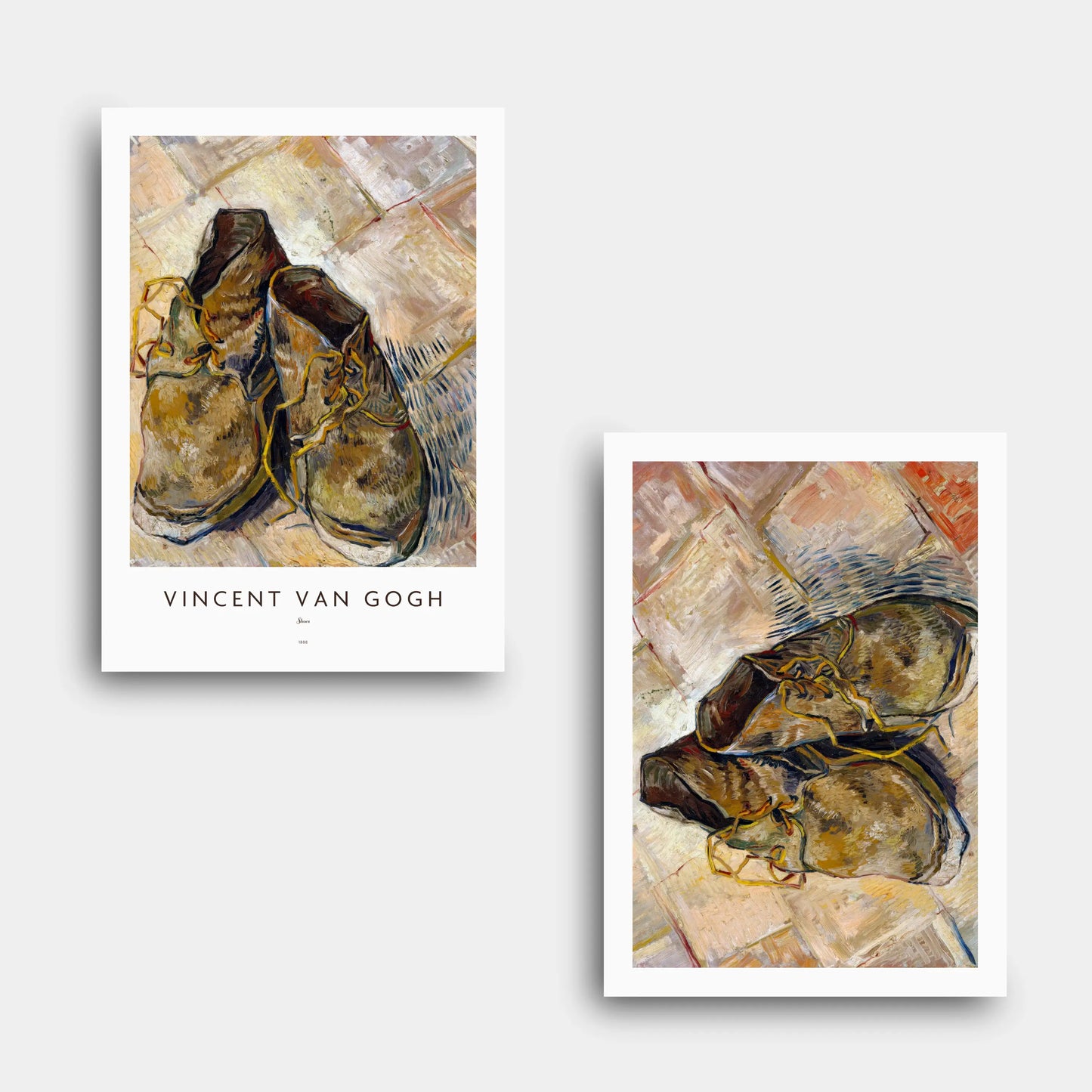

Vincent van Gogh - Shoes (1888) - Digital File N203

Vincent van Gogh - Shoes (1888) - Digital File N203

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Paper Poster | Canvas Print | Digital File

1. Historical and Artistic Context

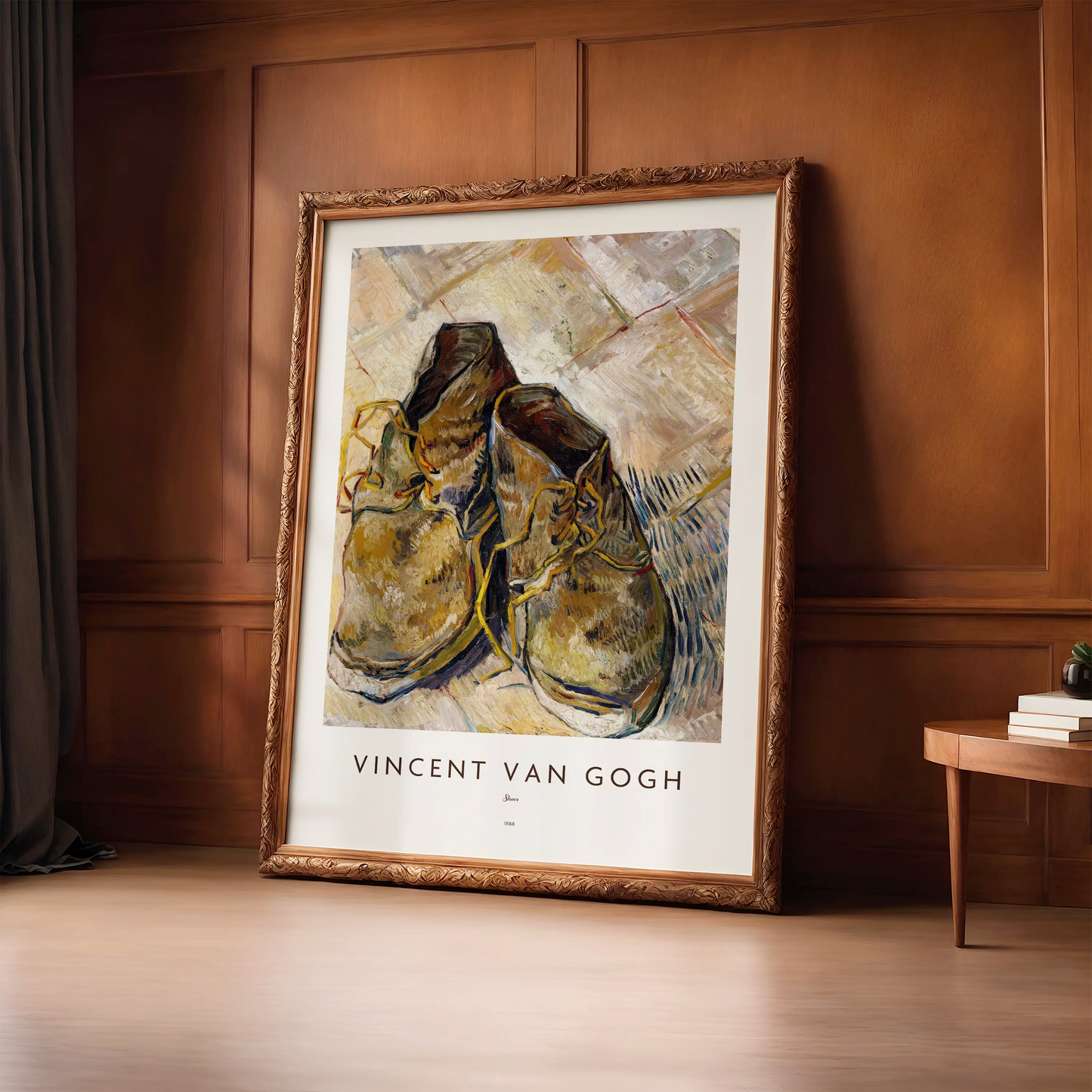

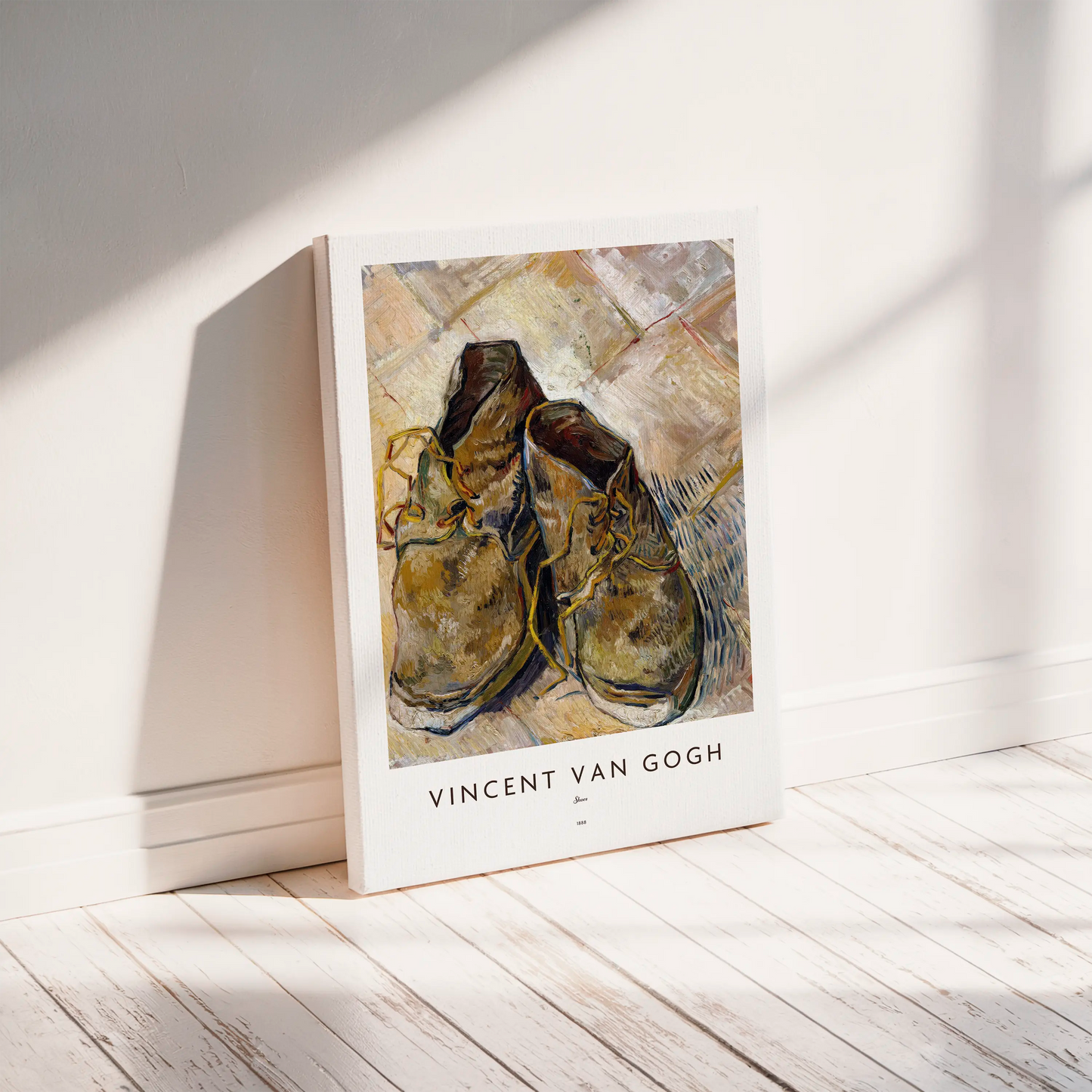

Vincent van Gogh painted Shoes in 1888 during his productive stay in Arles, a period marked by intense creativity and experimentation. While living in the Yellow House, Van Gogh sought to create an artist community, but while waiting for Paul Gauguin’s arrival he focused on still lifes and portraits. The worn boots placed on the red-tiled floor of his studio exemplify his fascination with humble objects that embody human struggle and endurance. The choice of such a subject reflects Van Gogh’s empathy for peasants and laborers, as well as his own restless, wandering existence. In contrast to traditional still lifes of luxury, this work elevates the ordinary, making it a poetic emblem of human life.

2. Technical and Stylistic Analysis

The composition is direct: two heavy boots lie casually yet monumentally on the ground. Van Gogh used thick, energetic brushstrokes, layering earthy browns and blacks to describe the cracked leather, while the floor glows with reds and yellows. The rough impasto makes the shoes tactile, as if the viewer could feel the worn surfaces. The diagonal strokes of the floor create depth and dynamism, anchoring the boots within space. Van Gogh’s Post-Impressionist style shines through in his use of bold, contrasting colors and expressive brushwork, transforming the mundane into a vibrant presence. The shoes appear almost alive, charged with the energy of the painter’s hand.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

The shoes symbolize labor, endurance, and the passage of time. Their worn state suggests long journeys, toil, and the life of the working class that Van Gogh admired. Some scholars argue they may have belonged to the peasant Patience Escalier, while others believe they were Van Gogh’s own, turning the still life into a silent self-portrait. Philosophically, Martin Heidegger saw in the painting the essence of peasant existence, while Meyer Schapiro countered that the work was autobiographical. Jacques Derrida later emphasized the ambiguity of meaning, asking “Whose shoes?” For many viewers, the painting embodies universal ideas of hardship, resilience, and absence, resonating across cultures and disciplines.

4. Technique and Materials

Van Gogh painted with oil on canvas, using a coarse weave that enhanced texture. He employed earth pigments such as ochres, umbers, and black for the leather, and warm reds and yellows for the tiled floor. Technical studies reveal that some pigments, particularly reds, have faded with time, altering the original vibrancy. Brushstrokes vary: short, curved lines describe the leather’s folds, while broader diagonal strokes define the floor. Shadows are suggested by streaks of darker paint rather than smooth modeling. Van Gogh’s urgent technique, applying paint thickly and directly, reflects his emotional intensity and his aim to give the shoes a presence far greater than their humble reality.

5. Cultural Impact

Though modest, Shoes has had remarkable cultural resonance. Beyond Van Gogh’s admirers, it became central in philosophical debates about art and meaning. Heidegger’s essay elevated the work as an example of art’s ability to reveal truth, while Schapiro and Derrida kept the debate alive in art history and theory. Today, the painting appears in countless textbooks and courses, symbolizing how art can transcend its subject. For ordinary viewers, the boots embody shared human experience: the weight of journeys, the dignity of work, and the poetry of the everyday. This cultural afterlife has made Van Gogh’s worn shoes some of the most discussed objects in modern art.

6. Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

Initially, the painting was little remarked upon compared to Van Gogh’s landscapes and portraits. It gained prominence in the mid-twentieth century, when Heidegger’s interpretation thrust it into the spotlight. Schapiro’s rebuttal reframed it as personal rather than philosophical, and Derrida’s deconstruction highlighted the impossibility of a single meaning. Since then, scholars have explored psychoanalytic, feminist, and cultural readings, each revealing new perspectives. The consensus is that Shoes exemplifies the richness of interpretive possibility. Its simplicity invites projection, and its ambiguity ensures ongoing relevance. Critics now see it as a masterpiece not only of Van Gogh’s art but also of art’s interpretive history.

7. Museum, Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh’s death, the painting passed to his brother Theo, then to Theo’s widow Johanna van Gogh-Bonger. In 1910, Helene Kröller-Müller purchased it for her renowned collection. Later, it traveled through her family, dealers, and eventually to Siegfried Kramarsky in New York. In 1992, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired the painting with funds from the Annenberg Foundation, where it remains today. The painting has traveled extensively, appearing in early retrospectives across Europe and in a major American tour during the 1930s. Its inclusion in these exhibitions helped introduce Van Gogh to global audiences, making the humble boots part of his international legacy.

8. Interesting Facts

1. Van Gogh painted several versions of shoes, in Paris, Arles, and Saint-Rémy.

2. He sometimes bought old shoes at flea markets and wore them in mud to age them before painting.

3. The red pigment in the floor has faded, changing the painting’s original look.

4. Heidegger never specified which shoe painting he analyzed.

5. Schapiro argued the shoes were Van Gogh’s own, not a peasant’s.

6. Derrida famously asked, “Whose shoes?”

7. The painting was once part of the Kröller-Müller collection.

8. It traveled widely in North America in the 1930s.

9. The Met calls it an icon of modern art.

10. Van Gogh signed this still life, an indication of its importance to him.

9. Conclusion

Van Gogh’s Shoes (1888) demonstrates how a simple subject can become endlessly meaningful. Through bold brushwork and earthy colors, he transformed worn boots into a symbol of labor, journey, and human existence. Philosophers, historians, and critics have debated its meaning, turning it into one of the most discussed paintings in modern thought. Its provenance and exhibitions testify to its recognition, while its cultural impact continues to expand. Ultimately, the painting reminds us that art need not depict grandeur to be profound. In two battered boots, Van Gogh captured the essence of resilience and the poetry of the everyday, leaving a lasting legacy for generations to contemplate.