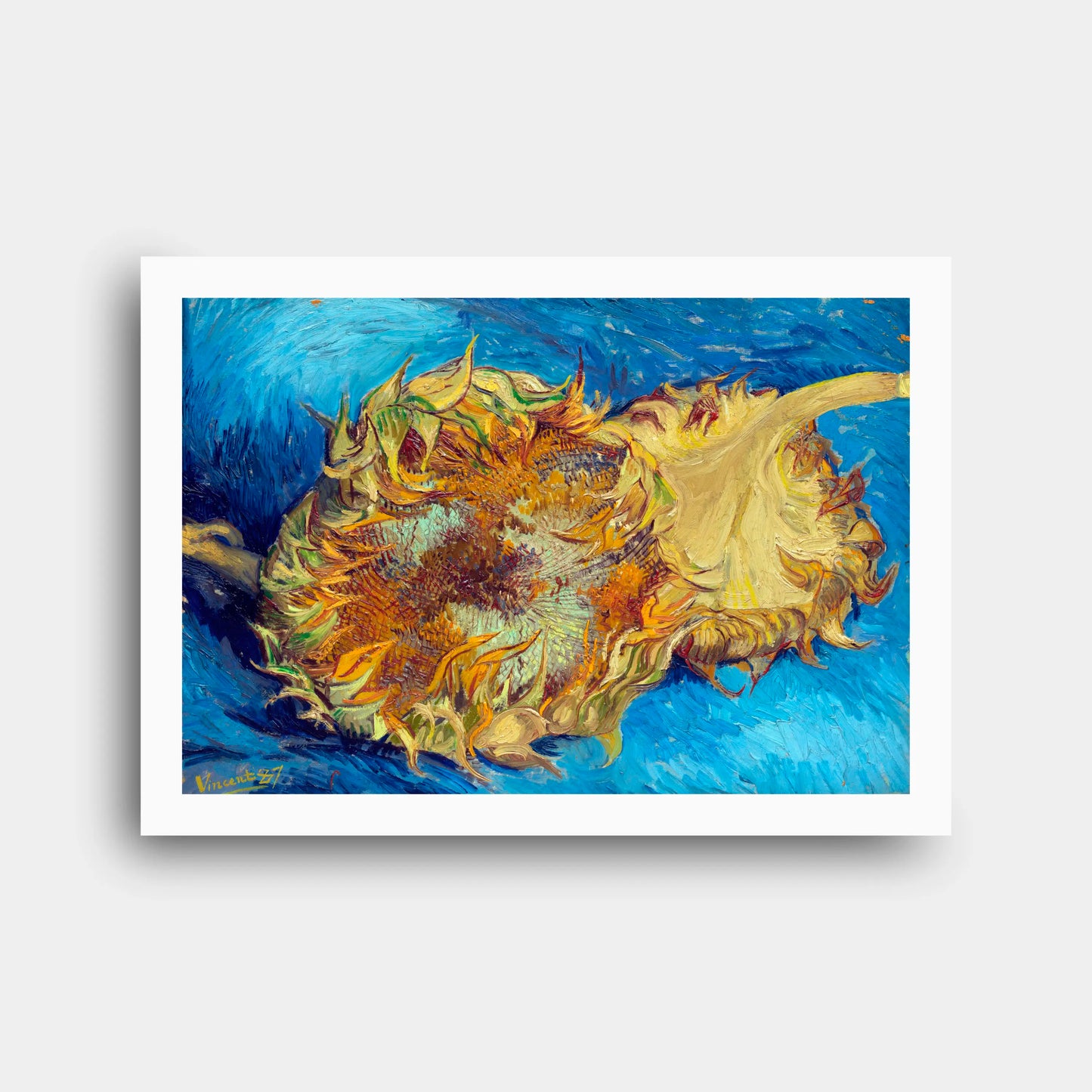

Vincent van Gogh - Sunflowers (1887) - Paper Poster N202

Vincent van Gogh - Sunflowers (1887) - Paper Poster N202

Couldn't load pickup availability

Share

Paper Poster | Canvas Print | Digital File

1. Historical and Artistic Context

Vincent van Gogh painted Sunflowers in 1887 during his Paris period, a transformative phase when he shifted from the dark, earthy tones of his Dutch years to a bold, luminous palette inspired by Impressionism and Japanese prints. Living with his brother Theo, he encountered Monet, Pissarro, Seurat, and Gauguin, whose influence led him to embrace complementary color and freer brushwork. In late summer 1887, he created four still lifes of cut sunflower heads, a subject considered coarse and unfashionable at the time. For Van Gogh, however, the sunflower became his personal emblem. He declared, “If Jeannin has the peony and Quost has the hollyhock, then I have the sunflower.” These works were also his first deliberate step toward making a single motif central to his artistic identity.

2. Technical and Stylistic Analysis

The composition of the 1887 Sunflowers is strikingly direct: two cut sunflower heads lying diagonally across a blue surface. One faces forward, exposing its seed disc ringed with curling petals, while the other shows the flower from behind. This dual perspective creates movement and variety. Van Gogh’s brushwork is heavy and expressive, using impasto to build texture. The seed discs are layered with ochre, umber, and green, producing a velvety density. The petals are painted with swirling strokes of yellow and orange, described by Gauguin as resembling “tongues of fire.” The complementary clash of yellow against blue generates intensity, making the flowers vibrate with energy despite their wilting forms.

3. Symbolism and Interpretation

The painting carries multiple layers of symbolism. The wilted flowers serve as a memento mori, reminders of the transience of life. Yet their brilliance suggests renewal and beauty in decay. Van Gogh associated sunflowers with gratitude and even envisioned them framing his portrait of a mother rocking a cradle, forming an altarpiece-like triptych about care and consolation. The flowers also symbolize friendship. Gauguin admired and acquired two sunflower paintings, and when Van Gogh later decorated his Arles studio, he filled Gauguin’s room with sunflower canvases as tokens of hospitality. More broadly, sunflowers symbolize loyalty, devotion, and the artist’s personal quest for light.

4. Technique and Materials

Van Gogh used oil on canvas, applying thick impasto with rapid, energetic strokes. His palette included chrome yellow for the petals, ochres and earth tones for the seed heads, and cobalt or ultramarine blue for the background. Some pigments, especially chrome yellow, have darkened over time, but the contrasts remain vivid. Van Gogh mixed his greens from yellows and blues rather than using pure pigments, creating natural tonalities. His brushwork varied: stippled strokes in the seed centers, curling lines in the petals, and broader strokes in the background. The materiality of the paint communicates urgency, making the process inseparable from the subject.

5. Cultural Impact

The sunflower paintings became icons of Van Gogh’s art and symbols of modernism. They inspired the Fauves and Expressionists, who admired his daring color. In Britain, the 1910 Post-Impressionist exhibition introduced them to a wide audience. Over time, the sunflower became synonymous with Van Gogh, appearing in countless reproductions, postcards, and cultural references. At Van Gogh’s funeral in 1890, friends placed sunflowers on his coffin, cementing the flower as his personal symbol. In the 20th century, one version sold for a record-breaking price, highlighting their global significance. Today, they embody resilience, hope, and the enduring power of art.

6. Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretations

During Van Gogh’s life, the sunflower paintings were little noticed except by Gauguin, whose admiration gave them importance. After Van Gogh’s death, critics and historians recognized them as masterpieces of expressive color and symbolism. Julius Meier-Graefe and Meyer Schapiro highlighted their emotional depth, while later scholars analyzed their technical daring and symbolic layers. Debates continue over whether Van Gogh intentionally encoded symbolism or whether meaning arose from his engagement with nature. Most agree the sunflowers serve both as technical experiments and profound expressions of gratitude and friendship.

7. Museum, Provenance and Exhibition History

The 1887 Sunflowers now resides in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Originally painted in Paris, it was exchanged with Gauguin, who hung it above his bed. In 1896, Gauguin sold it through Ambroise Vollard, after which it passed to Cornelis Hoogendijk in the Netherlands, later to Alphonse Kann in France, and then to Richard Bühler in Switzerland. It was co-owned with dealer Justin Thannhauser before The Met purchased it in 1949. It has since appeared in major exhibitions, including Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South (2001–2002). Today, it is displayed in Gallery 825 and rarely leaves the museum due to conservation concerns.

8. Interesting Facts

1. First Van Gogh paintings devoted solely to sunflowers.

2. Gauguin valued them highly and displayed them above his bed.

3. Painted wilting flowers rather than fresh blooms.

4. Gauguin described the petals as “tongues of fire.”

5. Van Gogh linked them with gratitude and consolation.

6. Chrome yellow pigments have partially darkened.

7. Sunflowers were placed on Van Gogh’s coffin.

8. The Met acquired the painting in 1949.

9. It was part of small café exhibitions in Montmartre.

10. Became a universal symbol of Van Gogh himself.

9. Conclusion

The 1887 Sunflowers is not just a still life but a turning point in Van Gogh’s career. Historically, it marked his Paris transformation; technically, it demonstrated bold impasto and color. Symbolically, it conveyed gratitude, mortality, and friendship. Its cultural impact has been vast, shaping modern art and embedding itself in popular imagination. Critically, it is viewed as both a technical experiment and an emotional declaration. Its provenance adds to its significance, and its enduring presence in The Met ensures its legacy. Through these cut, radiant blooms, Van Gogh expressed his search for light, his devotion to friendship, and his belief in finding beauty in transience.